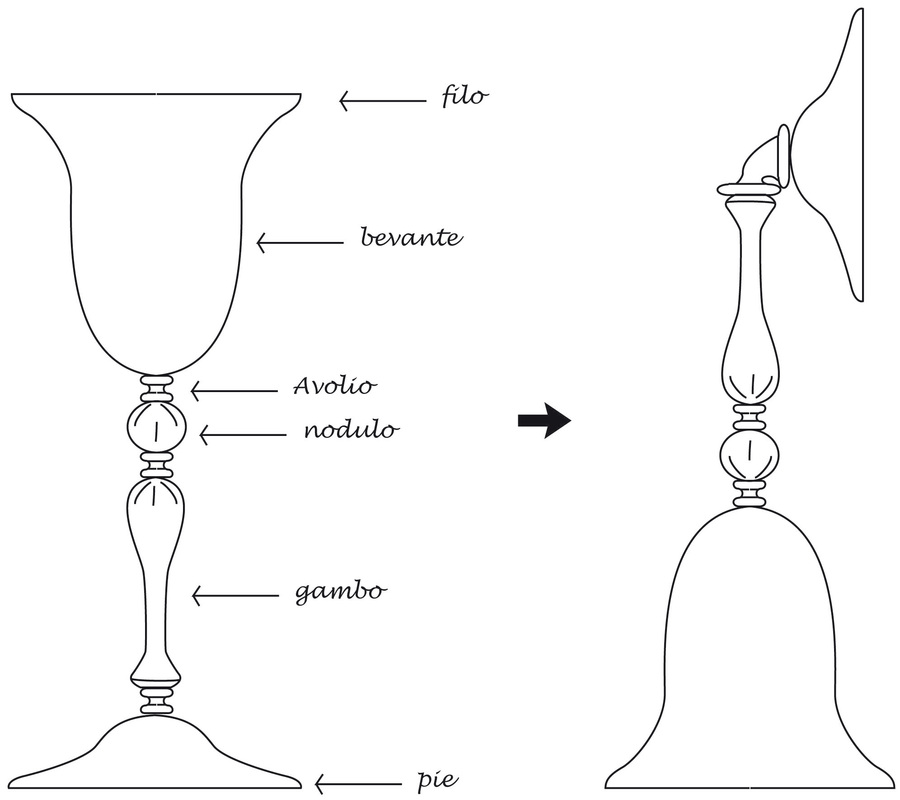

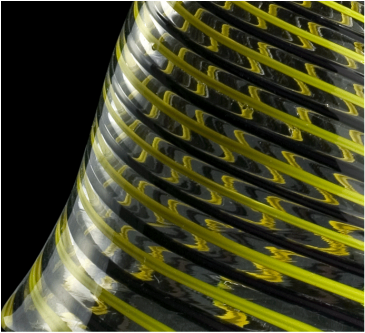

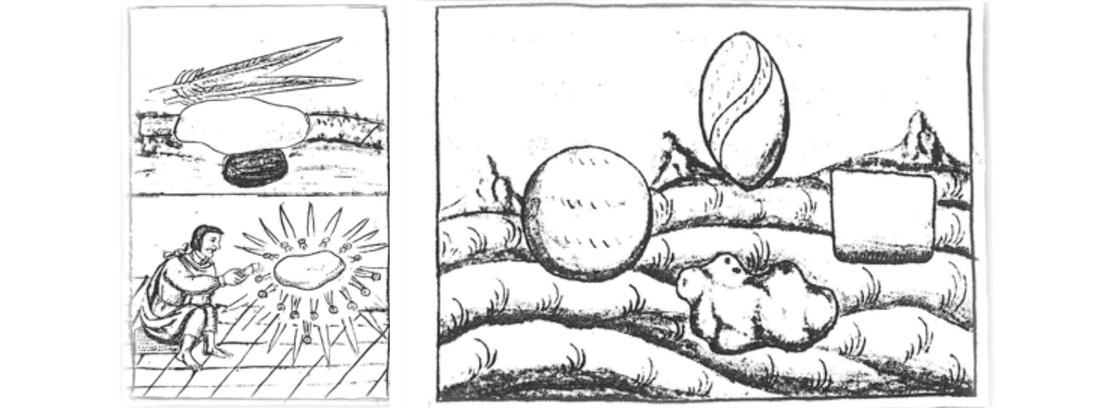

Este texto reúne datos muy interesantes fruto de una entrevista de carácter personal que sostuve con João Neto, director del Museo de la Farmacia de Lisboa, en Portugal, el 8 de junio de 2017, quién me explicó el origen de lo que en México conocemos bajo el nombre de "ojos de boticario". Estos tienen como antecedentes a los llamados “globos de mostrador” (Show globes), piezas muy relacionados al mundo de los alquimistas ingleses quienes practicaron la medicina química desde el siglo XVI. En esta época, los alquimistas, o "quimistas", ejercían su profesión bajo un aura de misterio y magia pues la gente no diferenciaba entonces su forma de hacer medicina en comparación con los boticarios (apothecaries) quiénes solo trabajaban con productos naturales. La medicina química se consolidó hasta el siglo XVIII en Gran Bretaña tras una cruenta guerra civil entre boticarios y químicos que terminó a finales del siglo XVII. Durante este período los químicos tuvieron que ser muy discretos en cuanto a su práctica pues podían ser acusados de brujería, y es así como los “globos de mostrador” se convirtieron en un símbolo de ésta, ya que eran colocados en los aparadores de las boticas de quienes secretamente ejercían la medicina química. Este símbolo los diferenciaba también de los boticarios, quienes se distinguían bajo el “mortero con mano”. Cómo sabemos, la alquimia se representa desde tiempos antiguos con los cuatro elementos: la tierra, el fuego, el aire y el agua, es por esto que los “globo de mostrador” se conformaban originalmente de 4 esferas de vidrio separadas, que embonan entre si construyendo una torre. La primera esfera presenta una base de cristal y un cuello, mientras que las esferas subsecuentes van reduciendo en volumen y presentan cuello en la parte superior y un tapón (stopper) en la parte inferior el cual embona en el cuello del globo que lo precede. La cuarta pieza es el tapón en vidrio solido transparente con forma de gota que corona la torre. Se rellenaban con líquidos de colores que se hacían con recetas y mezclas químicas, el resultado era muy llamativo, y aparentaba ser un elemento meramente decorativo, pero en realidad anunciaban por medio de su código cromático que en el establecimiento dónde se apreciaban se producían medicamentos químicos. El código ocupaba las cuatro piezas de cristal, ya que cada color representaba un elemento determinado: el rojo carmesí=fuego, el amarillo=tierra, el transparente=aire y el azul=agua.

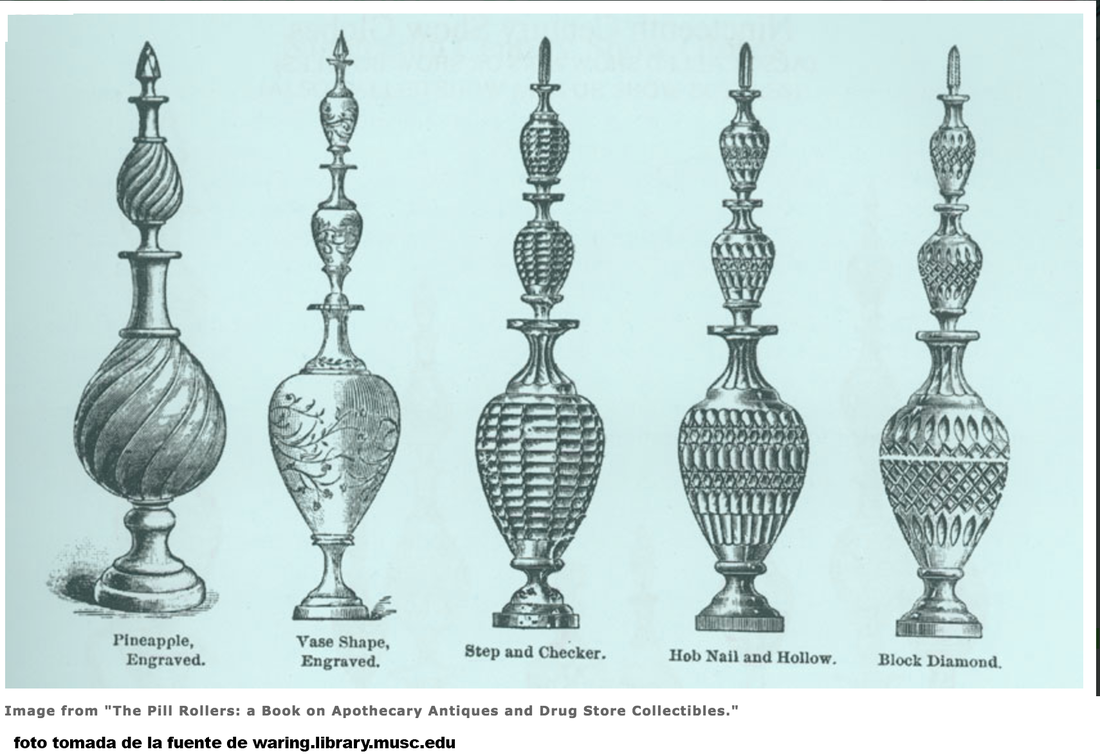

En el artículo "Mysterious Show Globes of the Apothecary", se describe como los “globos de mostrador” fueron introducidos en los países bajo la influencia británica, como Estados Unidos, Canadá, Australia y Nueva Zelanda y posteriormente pasaron al resto del mundo. También explica que era común verlos incluidos en los catálogos de mercancía americana, por ejemplo, el de la compañía Bullock & Crenshaw que presentó la primera colección extensa de ilustraciones de equipo de farmacia en la década de 1850 y ya para 1890 eran producidos y vendidos por varios fabricantes estadounidenses, entre ellos Whitall-Tatum Company, quienes lanzaron nuevas propuestas variando la forma, las decoraciones, el número de elementos y hasta el relleno interior mediante la incorporación de iluminación de gas o aceite desde el interior, sirviendo como precursores del letrero de luz neón.

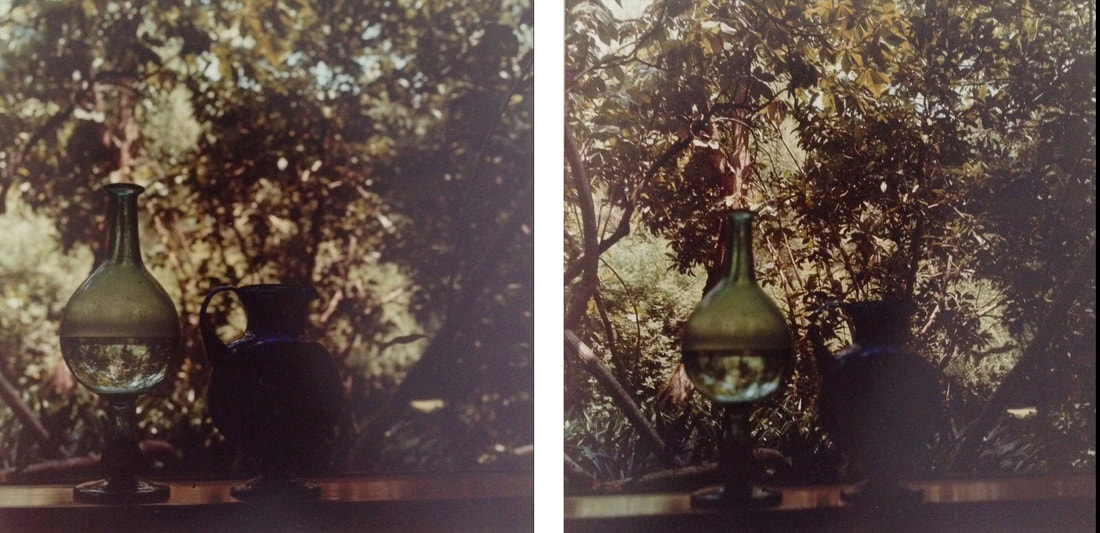

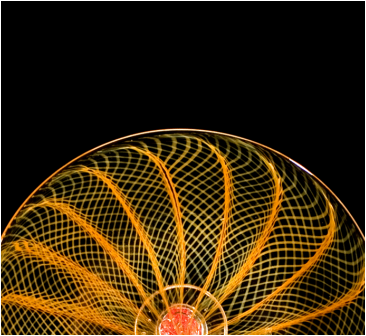

Durante la segunda mitad el s. XX las piezas d vidrio cobraron auge dentro de la decoración de las casas modernas mexicanas gracias a la influencia y gusto estético del arquitecto Luis Barragán Morfín y del pintor “Chucho” Reyes Ferreira. Con Chucho Reyes el código cromático adoptó un tono nacionalista al rellenarlas con líquido color rosa mexicano y con el arquitecto, un tono purista pues rellenaba con agua el contenedor hasta obtener una imagen invertida en el globo. El diseño de las piezas de vidrio fabricadas en México fue variando en número de elementos y presentación, aquí se soplaron dentro de moldes ópticos, y se hicieron con vidrio de color, así podían prescindir de llevar líquido al interior e incluso se hacían con la reconocida técnica local del burbujeado, pero siempre se mantuvo constante la forma esférica de los globos y de ahí el nombre que se les dio: "Ojos de boticario". -(arriba) Ojo de boticario de un solo elemento con vista al jardín desde el comedor de Luis Barragán. Fotografías de José Andrés Aguilar Vela, Casa Museo Luis Barragán. Marzo 2015. |

Valeria FlorescanoLives and works in Mexico City. Archives

July 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed