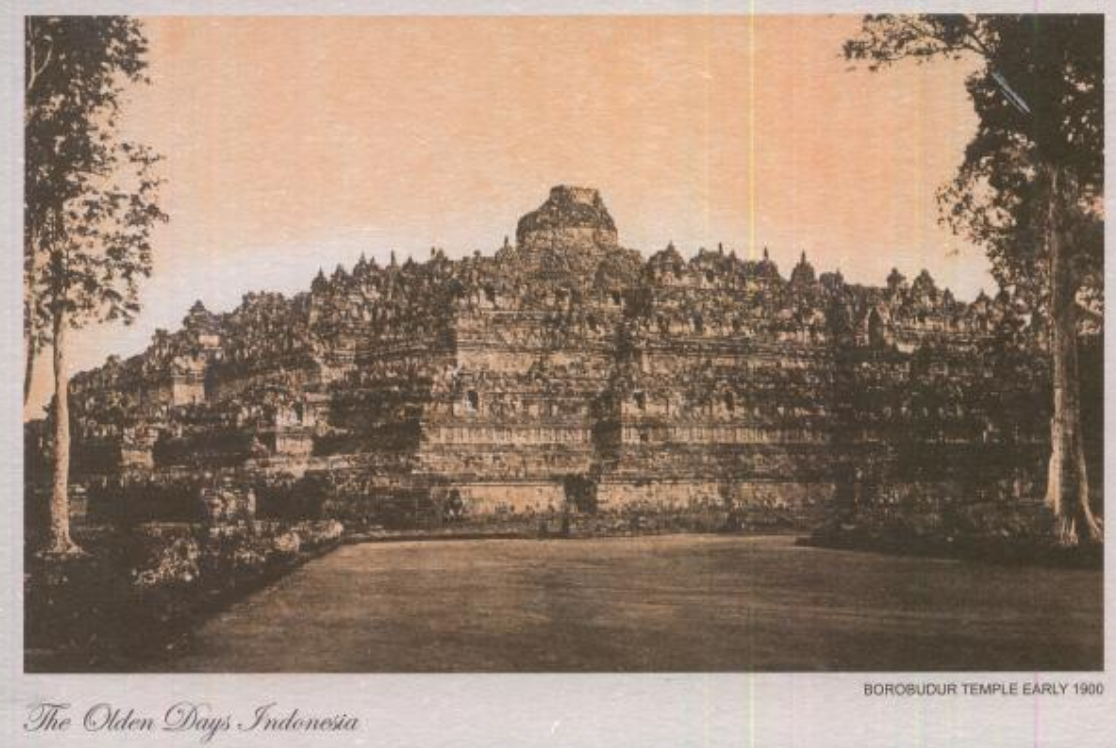

Borobudur, world heritage site in central Java, Indonesia. Vintage postcard. A trip to the Buddhist temple of Borobudur in Java years ago had been ringing in my head until recently I realized why my visit to the site turned to be such an enthralling memory, because of the intimate kinetic experience it implied and how it affected my perception. Retracing the journey, I recall the architecture and sculpture revealing a dialogue between ornament and abstraction understood by ancient cultures. The architectural plant of Borobudur symbolizes the sacred Mount Meru, center of the Buddhist Universe, it is raised ten levels above the ground, and each of its terraces represent a phase in the spiritual journey of the Buddhist doctrine. On arrival, one is recommended to ascend it following the pradaksina, the ritual of circumambulation of the temple as performed by Buddhist pilgrims. In order to do so, one has to keep the temple facing to the right side of the body following a clockwise direction. Entering the angular corridors at the base with panels full of scenes in bas-relief, one can´t help but feeling a little overwhelmed amid all the ornamentation. Gradually as one moves up, the corridors give way to more space at the third section of the temple representing a higher level of abstraction called Arūpadhātu, or the "kingdom without form". At this stage, ornamentation has been replaced by pure concrete forms, and one can see the geometry sharpened by its shadows under the intense Javanese light. The upper terraces have also discarded the angular edges seen on the first levels and replaced them with soft concentric oval corridors, in here, one walks between bell-shaped stupas harmoniously distributed along the way, their stone walls depicting a lattice pattern that opens its interior revealing a cross legged Buddha teaching a mudra. Panel de vidrio fusionado y termoformado. Valeria Florescano. Detalle de la vista brillante. Almost at the top, the experience is amplified by our sense of consciousness as we notice our breath and perspiration increase reminding us of our bodily presence. Eventually, one encounters the very large bell-shaped stupa that crowns the top, the soft lines of its walls appear clean of the lattice pattern appreciated in the previous level. Here we stand facing a clear exemplification of simplicity. It somehow reminded me when Joaquín Torres-García would emphasize on the use of abstraction, not as an escape from representation but as one of its multiple manifestations.[1] Reaching the summit of Borobudur, is equivalent to attaining enlightenment (the Nirvāṇa). Here, our eyes naturally gaze upwards addressing the blue sky and we can finally turn our back to the temple and connect with the surrounding landscape. To me, Borobudur is an example of architecture as a metaphor of humanity and how it elaborates a world under the manifestation of its beliefs. The complex spiritual lesson that the Javanese have bequeathed us with this site is invaluable. In here, movement and transition are used in a symbolic way to reach the light. It is a unique symbolic creation in the form of a sanctuary, and must have played an important role in ancient cultures. Walking through the architectural “story-line” represented in Borobudur has been one of the few spiritual transitions of mind and body I have ever experienced. Only equal to walking the tunnel of the underworld under the pyramid of Quetzalcoatl in Teotihuacán, México. In both examples, abstraction is better understood because of its proximity to ornamentation and not by the negation of it. To read this, active work by the observer is required, as well as an awareness of our own motor and sensory experience. It is also important to note that all symbols seen in these manifestations have meaning, so it should be more appropriate to refer to them as "emblems" rather than ornaments, but it is clear that with the passage of time and the lack of knowledge to understand their meanings, answers are lost and therefore the conceptual idea is somehow interrupted.  During the same trip, I found in a small craft shop, an english edition of Miguel Covarrubias' ethnographic and artistic work "The Island of Bali" which I immediately bought and turned out to be an indispensable companion that helped me dissect, understand and appreciate the very rich material culture of Indonesia. It is no coincidence that in this text I cite, two unique Latinamerican artists: the Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-García and the Mexican Miguel Covarrubias, both are important references to the subject of art, materials and craft. They shared a strong spirit of synthesis, and both experienced the condition of being foreigners, artists that had “traversed” into other lands, they also had a deep interest in academia and in understanding the material expressions of “ancient original cultures”, studied them passionately and had the ability to systematize and disseminate this ideas into serious texts. Both artists built a solid and personal body of work, García-Torres even coined a phrase that defined his own sculptural work as “an archeology of forms”[2] underlining the importance of the recognition of the past. Summing up, the “craft of making with the hands” involves perseverance, effort, vision, memory and movement. In craft, rhythm and process are one, that is why Borobudur remained such a symbolic passage in my memory, it triggered the common place: the journey between the abstract and the ornament. ¿Why, the term conceptual is mostly identified with the contemporary and not with the indigenous? A handmade piece coming from any background, be it an urban context or immersed in tradition is an expression of a symbolic world through manifested or abstract transformations. and as Covarrubias and Torres-García have demonstrated, it just requires a broad amount of knowledge from the viewer, an angled perception outside the box and a pinch of humility to start the journey . [1] Pp. 28. Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2015. Pérez-Oramus, Luis , Alberro Alexander, Chejfec Sergio et al. [2] Pp. 15. Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2015. Pérez-Oramus, Luis , Alberro Alexander, Chejfec Sergio et al. Panel de vidrio fusionado y termoformado. Valeria Florescano. Detalle de la vista termoformada. (texto en español)

Borobudur: el viaje entre la abstracción y el ornamento. Un viaje al templo budista de Borobudur en Java años atrás había estado sonando en mi cabeza hasta hace poco. Me he dado cuenta de que mi visita al sitio se convirtió en un recuerdo importante debido a una íntima experiencia cinética y cómo ésta afectó mi percepción. Recuerdo que la arquitectura y la escultura del templo establecen un diálogo entre el ornamento y la abstracción entendido por las culturas antiguas. La planta arquitectónica de Borobudur simboliza al sagrado Monte Meru, centro del Universo Budista, que se eleva diez niveles sobre el suelo, y cada una de sus terrazas representa una fase en el camino espiritual de la doctrina budista. Al llegar, se recomienda subir siguiendo la pradaksina, el ritual de circunvalación del templo realizado por los peregrinos budistas. Para ello, hay que mantener siempre al templo del lado derecho del cuerpo y subir en dirección del sentido de las agujas del reloj. Recuerdo caminar por los corredores angulares de la base, densamente adornados de paneles con escenas en bajo relieve, uno se siente un poco abrumado metido entre tanto ornamento. Poco a poco, y a medida que uno se mueve hacia arriba, los pasillos abren más espacio hasta llegar a la tercera sección del templo que representa un nivel superior de abstracción llamado Arūpadhātu o el "reino sin forma". En éste nivel, la ornamentación ha sido sustituida por formas concretas puras, donde se aprecia una geometría afilada por su propia sombra bajo la intensa luz javanesa. Las terrazas superiores también han descartado los bordes angulares de los primeros niveles y los reemplazan por suaves corredores ovalados y concéntricos, aquí, uno camina entre estupas en forma de campana armoniosamente distribuidas a lo largo. Sus paredes de piedra presentan un patrón de rejilla que al abrir su interior revela un Buddha con las piernas entrecruzadas, enseñando un mudra. Ya casi en la cima, la experiencia se amplifica por la sensación de notar un aumento en la respiración y la transpiración que recuerda nuestra “corporeidad”. Eventualmente, encontramos a la gran estupa en forma de campana que corona la parte superior, las líneas suaves de sus paredes limpias del patrón reticular apreciado en el nivel anterior. Aquí estamos frente a una clara ejemplificación de la simplicidad. De alguna manera me recordó cuando Joaquín Torres-García enfatizaba en el uso de la abstracción, no como un escape de la representación, sino como una de sus múltiples manifestaciones[1]. Llegar a la cumbre de Borobudur, equivale a alcanzar la iluminación (el Nirvāṇa). Aquí, nuestros ojos naturalmente miran hacia arriba abordando el cielo azul y finalmente podemos dar la espalda al templo y conectar con el paisaje circundante. Para mí, Borobudur es una muestra de la arquitectura como metáfora de la humanidad y de cómo ésta elabora al mundo bajo la manifestación de sus creencias. La compleja lección espiritual que los javaneses nos han legado con este sitio es invaluable. Aquí, el movimiento y la transición se usan de una manera simbólica para alcanzar la luz. Es una creación simbólica única en forma de santuario y debió haber desempeñado un papel importante en las culturas antiguas. Caminar a través de la "narración" arquitectónica representada en Borobudur ha sido una de las pocas transiciones espirituales que he experimentado en mente y cuerpo. Similar al caminar el túnel del inframundo bajo la pirámide de Quetzalcoatl en Teotihuacán, México. En ambos ejemplos, la abstracción se entiende mejor por su proximidad a la ornamentación y no por la negación de ella. Para entender esta sutileza, se requiere un trabajo activo del observador, así como una conciencia de su propia experiencia motriz y sensorial. También es importante apuntar que todos los símbolos que vemos en dichas manifestaciones tienen significado, por lo que sería más apropiado referirse a ellos como "emblemas" en lugar de ornamento, pero queda claro que con el paso del tiempo y la falta de conocimiento para entender sus significados, las respuestas se pierden y por lo tanto la lectura del concepto queda de alguna manera interrumpida. Durante el mismo viaje, encontré en una pequeña tienda de artesanía una edición inglesa de la obra etnográfica y artística de Miguel Covarrubias "La Isla de Bali", la cual compré inmediatamente y se convirtió en un compañero indispensable que me ayudó a diseccionar, comprender y apreciar la muy rica cultura material Indonesa. No es casualidad que en este texto cite a dos artistas latinoamericanos únicos: al uruguayo Joaquín Torres-García y al mexicano Miguel Covarrubias, ambos son referencias importantes respecto al arte, los materiales, y lo hecho a mano. Ellos comparten un fuerte espíritu de síntesis y ambos experimentaron la condición de ser extranjeros, artistas que "atraviesan" otras tierras, también porque tenían un profundo interés en la academia y en la comprensión de las expresiones materiales en las "antiguas culturas originales", las cuales estudiaron apasionadamente y tuvieron la capacidad de sistematizar y difundir sus ideas al respecto en textos serios. Ambos, construyeron también, un cuerpo de trabajo sólido y personal, García-Torres acuñó una frase que definiría su propia obra escultórica como "una arqueología de formas"”[2] subrayando la importancia al reconocimiento del pasado. Resumiendo, el "arte de hacer con las manos" implica perseverancia, esfuerzo, visión, memoria y movimiento. En el oficio, ritmo y proceso son uno, por eso Borobudur se convirtió en un pasaje tan simbólico en mi memoria, y desencadenó el lugar común: el viaje entre lo abstracto y el ornamento. ¿Por qué, el término conceptual se identifica principalmente con lo contemporáneo y no con lo indígena? Una pieza hecha a mano procedente de cualquier contexto, ya sea de naturaleza urbana o inmersa dentro de la tradición, es la expresión de un mundo simbólico a través de sus transformaciones manifiestas o abstractas. Y como nos lo han demostrado Covarrubias y Torres-García, solamente se requiere un amplio conocimiento por parte del espectador, una mirada oblicua fuera de la caja y de una pizca de humildad para iniciar el viaje.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Valeria FlorescanoLives and works in Mexico City. Archives

July 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed