|

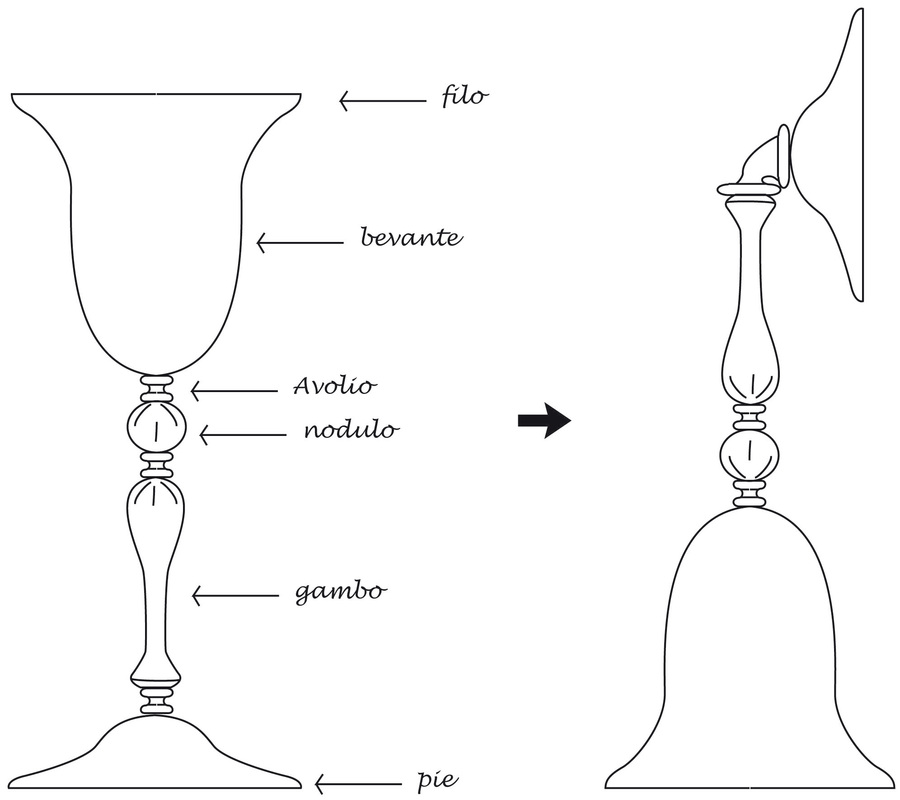

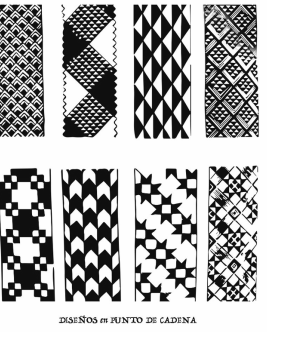

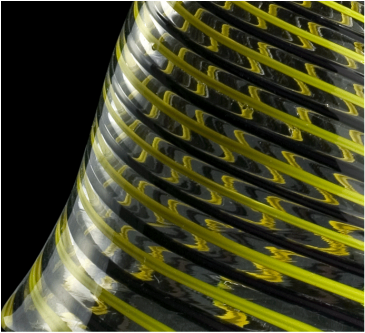

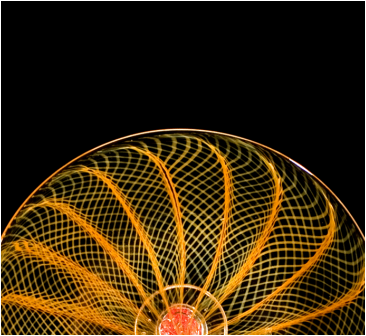

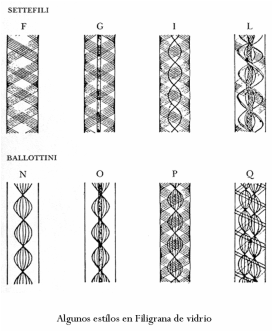

My glass work comes to be from a concern in contemporary practices with this material in the context of México. What has attracted me of working with this approach is the connections with the past as well as the conceiving of a future understandment of how everything is part of this unique conceptual and material landscape and how it reflects geography and history in all its cultural aspects. Therefore this perception acknowledges and strengthens a respect for all the things diverse.  Fig. 1. Tehuana Goblet detail. Photo: © lente 3030 The research that precedes the Tehuana Goblet project has its origins in two elements: a geopolitical point of view, where the isthmus and the archipelago exemplify a relationship of unity-diversity, and the crossing between east and west, as well as the evolution of higher sophisticated crafts intimately bonded by their own economical and cultural factors. Because the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is indeed a geographical crossroad, symbol and representation coexist in a multidimensional space. Lets not forget that this is the narrowest portion of México, and that during the XVIII century many explorers traveled there analyzing the possibility of building an inter-oceanic channel, a desition that later inclined for Panama. Likewise in Italy, the Murano island is part of the Venetian archipelago, and therefore a window to the east, so both locations share the characteristic of containing a uniqueness of its own, and the influence of being connected to other continents by the sea. Ever since its archetypal construction during the 1920´s, the Tehuana image has symbolized a mixture of beauty and resistance through identity, naturally portrayed by mexican artists. Much of this presence is due to her garment; the Tehuana traditional dress is a result of the conflation of many paths: it has prehispanic origins, and Asian traces linked to the Philippine and Chinese cultures, as well as some Flemish and Spanish accents. The Tehuana women use their traditional garb for special social occasions, like performing communitarian or religious rituals as well as for going to the marketplace. Because the women run the region´s commerce, the marketplace is one of the most relevant social institutions in this matriarchal society. As Annegret Hesterberg says “dressing traditionally exercises a form of representation that no modern attire can ever achieve” [1]. The dress consists of the following elements: a short sleeved shirt called "huipil", a skirt with a white plated finish and a lace underskirt, but most important of all, is the headdress, a spectacular confection of starched plated lace that frames the face like an aureole, called the "bida: niró" in zapotec, which is translated to "Resplandor" in spanish or “Gleam” in English. Fig. 2. Valeria Florescano, Antropomorphization of a venetian cup into a Tehuana goblet. Fig. 3. Charles B. Waite photo of a Tehuana woman, circa 1896. Tehuana goblet Photo © lente 3030. This translation of appearances -where reflection becomes luminosity, but also becomes beauty – is explored in the Tehuana goblet installation. There, I wanted to show the subtle relationship between the traditional garment of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region and a Venetian crystal chalice made in the style known as “Verre à la façon de Venise”. By altering each goblets into an anthropomorphic representation of the mestizo woman, the “Tehuana”. After each goblet is finished to all its detail, and while the piece is still hot at the gaffers bench, a final gesture is made; when I quickly bend the foot to a 90 degree angle on the side, until both ends of the “avolio” meet, this allows the foot to face sideways, thus reversing its standing point. The foot then resembles the headdress of the Zapotec women called the "bida:niró", which is translated to "Resplandor" in Spanish or “Gleam” in English. A spectacular confection of starched plated lace that frames the face of the woman like an aureole. This crossroads between east and west, show deep cultural roots and complexities, and are expressed in the richness and sophistication of the women´s dress through the presence of the embroidered velvets and starched lace brocades that conform the headdress, blouse (huipil), skirt, underskirt and apron. Connected with the geography of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, these proud women, in their traditional garment have inspired many artists such as Frida Kahlo and Sergei Eisenstein among others. Fig. 4. Miguel Covarrubias. a selection of designs for the huipil blouse from the book "México South". Fig. 5. and Fig. 6. Details of Tehuana goblets photo© lente 3030. Fig.7. Some Textures of vetro a filigrana techniques, and its categories: vetro a fili ( filaments), vetro a retorti (twisted filaments), and vetro a reticello (filaments forming a net). For the installation a series of glass goblets where blown, following traditional Venetian glass techniques and using canework patterns like "zanfirico", "reticello", or "latticino", this glass patterns ressemble the textile lacework. The goblets, become Tehuanas by placing them in an upside down position. This invertion changes the order of its components, but not its material language, therefore the cup becomes the base and ressembless the skirt. The stem, with its “avolio” [2] and node [3] decorations function as usual, holding up what used to be the foot, but now this becomes the ”Gleam” or headress of the Tehuana, an element that reveals the concentric movement in the filligree pattern and the reflection of light. In each goblet, I explored the idea of beauty, feminine seduction and diversity. I was also interested in highlighting the sensuous quality of the functional and sophisticated handmade objects, that is why every piece is loaded with information on its own history and use, creating a network of meanings and particularities but also speaking a common language that evolves around ritual and universal beauty. I was then able to symbolically follow the commercial trade route of lace and sumptuary glass from Renaissance Venice to Mexico, specifically to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca. Beginning with the fact that the strenght of the textile commerce in Venice during the Renaisance followed a reinterpretation in new techniques of glassmaking during the sixteenth-century in Venice because of the imitation of the lace frills with the invention of the filligrana techniques in Murano, (patented by Filippo and Bernardo Catani in 1527). Signaling both as common grounds between the isthmus and the island, where commercial and cultural exchanged symbols melted. and exemplifying the crossroads between East and West as well as the interlocking paths between the colonized and the colonizers. It is impossible to verify that Venetian textile trade influenced the invention of glass filigree; or even chart a trade route of Venetian glass into the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. But we can draw parables between these two geographies. The Glass chalices exemplify in the form of seduction and beauty , where usage and custom celebrate identity within the highest degree of sophistication. Underlining the sense that dressing in costume together with rite, reifies through practice, the Tehuana Goblet presents displacements, translations and migrations of objects in new orders. Fig. 8. Detail of Tehuana goblet by Valeria Florescano photo© lente 3030. This new objects relocate themselves against strictly separatist notions. Covering both territories; Venice and Juchitán, and placing together blown glass with the textile garment into a road of seduction. II . Glass Huipiles Claudio Linati, the italian artist who introduced lithography in México, must have fell in love with the women of the Isthmus. His Tehuana with a tight enredo (a kind of skirt consisting on a rectangular piece of cloth that wraps around the hips) and transparent huipil revealing her pretty breasts, broke the puritanical austerity of a long series of civil and military garments that Linati engraved in the second decade of the XIX century. The lace frills that frame the face of the young isthmus girl makes her nudity more notorious, because it is unexpected. After drawing so many thick layers of cloth skirts from head to toe, the artist delights himself with the light freshness of this vain girl. Upon her shoulders a glass gleam seems to float about. Perhaps its no coincidence that a man from Italy took such attention to the Tehuana garb. In this installation, Valeria Florescano unveils consonances between the delicate Murano goblets and the diaphanous bidaaniró’, the white gala head dress of the zapotec woman. Glass filigree, and starched lace thread; hand blown goblets at the bright crimson furnace, pleated hems with a very hot iron. But pointing out this obvious parallels does not make justice to the work of Valeria. Her curiosity leads us to subtle discoveries related to the form and texture of seduction. Linati ´s Tehuana flirts amongst the goblets and the curling strands of glass remain awaiting the brush of her tanned skin. Alejandro de Ávila B. Curator. Museum of Textile, Oaxaca. Fig. 9. Detail of Tehuana goblet photo© lente 3030. Acknowledgements I am grateful for the assistance I have had from many people who have been walking alongside this process during its different stages, but mostly with kindness and support for my work. Thank you; friends, collaborators and collectors: Treg Silkwood, Candance Martin, Mónica Bárcena, Javier Sánchez Carral, Ana Paula Fuentes, Valeria Vallarta Siemelinck, Johanna Angel Reyes, David Israel Perez Aznar, Alfredo López Austin, Alejandro de Ávila, Olga Margarita Dávila, Iris Sosa, Manuel Rocha Iturbide, Jason Pohl, Angel Miquel, Catarina Carvalho, Teresa Almeida, and Krzysiek Kucharczyk. I’m also extremely thankful for having great people collaborating at my “Fuego conJuego” studio: Ena Lehman, Daniela Suchil and Alfonso Chagoya, as well as my work companions from “Arta Cerámica”, you all make studio work a collaborative space full of respect, motivation and playfulness: Gloria Rubio, Ana Gómez, Marta Ruiz and Fabricio Tomé. I also want to thank other crafts people and artists, with whom I worked through this process: Rolando Regino Porrás, his wife Lorena Lávida and Javier Pantaleón. Last, but not least, I want to thank all of BWA Gallery staff in Wroclaw, Poland, specially Tomek Cugier and Dominika Drozdowska, as well as Alejandra Barajas at the Secretaria de Relaciones Exteriores (SRE) in México City. Finally I want to thank my friends who are besides me no matter what and always inspire me with their own doings: Angélica Moreno, Sarah Gilbert, Graciela Iturbide, Ryan Staub, Nicola López, Rocío Mireles, Remigio Mestas and Tessy Ades,Thank you! Also my very talented and supporting family who encourages me every day: I couldn´t have done this without your love and presence: Enrique Florescano, Alejandra Moreno Toscano, Carmen Moreno Toscano and my daughter Camila. Valeria Florescano , Mexico City, November 2015. [Foot Notes] [1] Hesterberg, Annegret, “Presencia compartida - Una segunda piel” en Artes de México, no.49 (“La Tehuana”), México, 2000, p.41 [2] Avolio: (Italian) A small quantity of glass that joins the stem and the foot of goblets and similar forms. [3] Node: (Latin nodus, ‘knot’) is either a connection point or a redistribution point.

2 Comments

4/21/2016 04:00:40 pm

Thanks for publishing this Valeria, it adds new dimensions to the contemporary glass practice. And we understand a little better the spell cast by colonialism. Splendid!

Reply

11/23/2019 04:19:47 pm

I was also present at this convention. To be honest, I did not expect much from it, however, I did have a lot of fun. Not only are the people amazing, but the event was also filled with great booths. I was able to win a lot from the booths, and I just want to go back there. This is a two day convention, so I expect a lot of things for the next day, I hope that they meet my expectations.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Valeria FlorescanoLives and works in Mexico City. Archives

July 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed